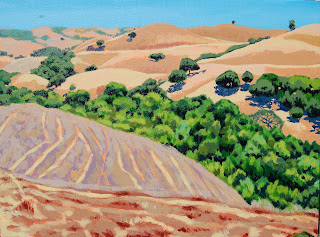

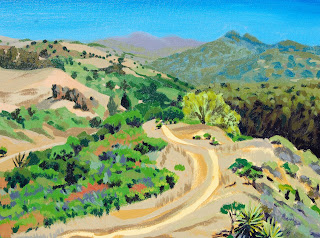

Lately, maybe because the good weather beckons, or because everyone else seems to be doing their summer traveling, I've been painting outdoors by myself quite a bit. I might bring watercolors, oils, or more recently, acrylics. My setup is not too complicated. By now I have a system that enables me to get ready in about 15 minutes.

I carry a smallish canvas. If I am doing oils and the canvas is longer than 15 inches on any of its sides, I might attach canvas straps to the stretcher frame to facilitate transport without smearing. This is specially helpful under windy conditions, when oil paintings can be flipped off your hand in a nanosecond. You can attach the straps in "backpack" style. The canvas goes on a plastic and aluminum field easel that weights less than 3 pounds.

There used to be a time when I could sit on the floor for hours at a time. These days, I am happy to cart a variety of lightweight seating gigs, depending on how far away will I walk from my truck. I also enjoy the perspective they provide, otherwise all of my compositions would be done at floor level! I find folding aluminum/canvas seats comfortable and lightweight. They are also cheap. I have one which

doubles as a backpack, it's got pockets with zippers for supplies. The straps on this seat bag are flimsy, but I've walked with it without major problems. However, this is not the setup you want if you're cycling to your location. Because of those same flimsy straps, the seat bag tends to sway, destabilizing your moves.

If you're walking more than a couple of miles, or if you're taking your bike, you want

a regular backpack with a flap on top to secure your easel and seat tightly against your back. I have an old one that can get smeared with paint. It needs to feel comfortable if you're carrying several bottles of water (as when you use acrylics), and be waterproof if you are carrying watercolor paper. The ones at the art store tend to be too expensive.

When I first began painting solo, my family was concerned because I am female and not built like a wrestling champion. To avoid unwanted human attention, I try to find slightly-out-of-the-way spots where I don't have to worry about who is coming up behind me. I either sit with my back against a tree or fence, or I sit at a spot where I can see who's coming before they see me. Hilltops are great for this. I also began bringing a can of mace and a stick, for the ocassional off leash pit bull I might encounter in the regional park near my home. No problems so far, since considerate owners do not allow their dogs to stick their nose on my palette. There are mountain lions and other critters in these parts, but if I thought about this and other dangers, I would never paint.

My partner insists I take my fully-charged phone, some emergency money, and a first aid kit. I used to laugh it all off, but I've used the kit twice since I began carrying it. Once to help a cyclist who crashed in front of my eyes, and another time to disinfect my punctured fingers (I grabbed some rusty barbed wire). Allergic folks should bring either an epi-pen or their inhaler. Yes, I was stung by a wasp, four miles away from the parking lot. Speaking of insects, during the summer, flea bites seem to be a problem. Carry something for the itch, least you find yourself interrupting your painting every few minutes to scratch.

Nourishment should be a very simple affair. Normally, I take off right after a decent-sized meal. In this way, I will not need to snack for the next three hours. If you do need to snack, take something that comes in its own wrapper and does not need any prepping. Your hands will be full of wet paint, and in any case, you will be too absorbed to even pay attention to the food. Don't forget drinkable water, specially if you are working in very hot weather. It's amazing how time passes when you're distracted, and you could find yourself quite dehydrated simply because you forgot to drink. Or you could have used your drinkable water to paint, which is worse! Chances are your issues will be more with temperature than with thirst.

Take several layers of clothing. Here in the Bay Area, summer fog is preceded by cold wind in the afternoon, but if you live elsewhere, you may have to prepare for either sudden summer showers (flash floods?), or a depleted ozone layer. Wear sunscreen, or better still, a hat, long-sleeves and long pants. Forget the sandals. This is not nineteenth century Aix-en-Provence. If insects don't get to your toes first, they will likely become sunburned, specially at high altitudes.

One more thing: Polarized sunglasses. I cannot say enough good things about them. Mine are progressives, too. Your eyes will rest as you work and color perception is barely affected.

Painting solo can be a most rewarding experience, provided you think of your own comfort and safety before you leave. If you do get started, drop me a note. I'd love to read about your own adventures.

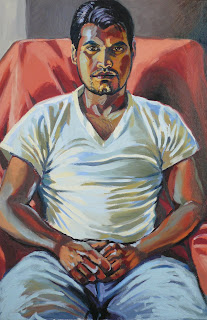

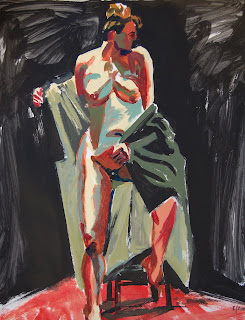

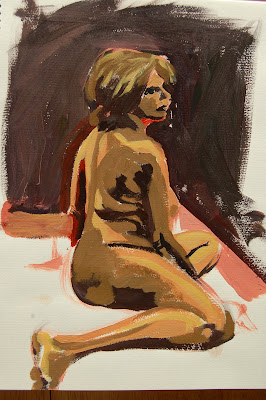

Pardon the quality of my images. To make a long story short, my laptop quit and my scanner broke down last month. I've had to edit images on a primitive image editor. We've been doing some short poses, and I've been stitching media to keep it all fresh. The color piece is acrylic, and the black and white piece was done in ink and grey watercolor. These are also smaller than what I've been doing previously, they are from a notebook I've been taking to my figure drawing sessions.

Pardon the quality of my images. To make a long story short, my laptop quit and my scanner broke down last month. I've had to edit images on a primitive image editor. We've been doing some short poses, and I've been stitching media to keep it all fresh. The color piece is acrylic, and the black and white piece was done in ink and grey watercolor. These are also smaller than what I've been doing previously, they are from a notebook I've been taking to my figure drawing sessions.