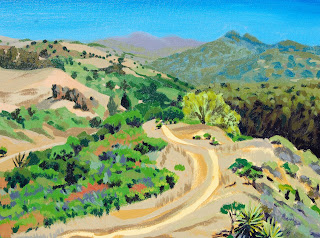

I took my acrylics to the field. I went to a highway about three exits down the freeway, took a less traveled road up the hills, parked the truck by a small tree by the road and looked down. There was no path and no way to walk beyond the road's edge unless I wanted to roll. So I went to three other roadside sites before I settled under a large, moribund bush, hidden from the high speed cars. It was noon and everything cast a sharp shadow. Hungry cows mooed near the creek I was certain existed down the canyon. Cyclists held their loud dialogues, oblivious to my presence. Another bush obstructed my view, but by now I had realized this was the best view I could hope for.

I took my acrylics to the field. I went to a highway about three exits down the freeway, took a less traveled road up the hills, parked the truck by a small tree by the road and looked down. There was no path and no way to walk beyond the road's edge unless I wanted to roll. So I went to three other roadside sites before I settled under a large, moribund bush, hidden from the high speed cars. It was noon and everything cast a sharp shadow. Hungry cows mooed near the creek I was certain existed down the canyon. Cyclists held their loud dialogues, oblivious to my presence. Another bush obstructed my view, but by now I had realized this was the best view I could hope for.Acrylic paint dries ultra fast, if all you've been using is oil for the past five years. Yet I was determined not to spend hours "...trying to breathe 'life', to breathe 'resonance' into an otherwise rather impersonal 'plastic'," in the words of Mark Jacobson. I had made my peace with acrylic in college, during assignments that forced me to start and finish a painting in a day. My issue was simply finishing in a period of two hours, and wresting with the lavender hill in the middle, which refused at all costs to yield the secret of its personality. I would have had this same struggle (or perhaps a worse one) had I been using oils, I reasoned. In the end I finished a satisfactory version of what I saw in my studio.

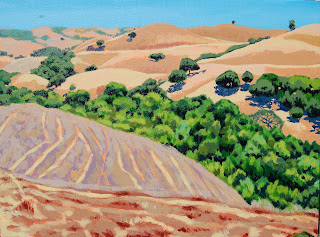

Earlier that week, I had been to the very familiar park behind my house, walked a few minutes past the gate, and found myself at the top of a small hill overlooking a path leading (where else?) into another creek. It was noon or shortly after noon, and I was wearing my polarized lenses,

hemp hat, and paint-stained shirt, looking exactly like those excentric middle-aged ladies I avoided in art school. It was windy and dry. Wasps had decided to check out my palette and I was so busy trying to tie a rock to my aluminum easel that I did not see the dog walker who slowly, subrepticiously, crept up to take a peek. She said hi. I said nothing, pretending I hadn't heard. Wasn't my look eccentric enough? I waved and she got the message. After taking one last good look, she walked away and I went back to the business of landscape worship. In this painting the only struggle was the combination of wind and dryness conspiring to prevent adequate color mixing. I was trying to keep in mind the words of Brad Faegre: "Time is not the enemy with acrylics. Think of the fast-drying characteristics of the medium as an invitation to paint and repaint, until you see something you like."

hemp hat, and paint-stained shirt, looking exactly like those excentric middle-aged ladies I avoided in art school. It was windy and dry. Wasps had decided to check out my palette and I was so busy trying to tie a rock to my aluminum easel that I did not see the dog walker who slowly, subrepticiously, crept up to take a peek. She said hi. I said nothing, pretending I hadn't heard. Wasn't my look eccentric enough? I waved and she got the message. After taking one last good look, she walked away and I went back to the business of landscape worship. In this painting the only struggle was the combination of wind and dryness conspiring to prevent adequate color mixing. I was trying to keep in mind the words of Brad Faegre: "Time is not the enemy with acrylics. Think of the fast-drying characteristics of the medium as an invitation to paint and repaint, until you see something you like."